LEO = Low Earth Orbit: Up to 2.000 km altitude.

MEO = Medium Earth Orbit: 2.000 – 35.000 km altitude.

GEO = Geostationary Earth Orbit: 35.786 km altitude.

|

Introduction These observations started in August of 1964. The reason was that after the French Space Research Organization (CNES) rocket launches were conducted earlier in the summer, Dr. Thorsteinn Saemundsson, astrophysicist with the High Altitude Research Department of the University of Iceland’s Science Institute and Dr. Agust Valfells, nuclear engineer and then Director of Iceland Civil Defense, attended a final review meeting with the French scientists, and other Icelanders who had supported them during the experiment. At that time Thorsteinn mentioned to Agust that he was looking for someone to conduct observations of trajectories of satellites crossing over Iceland. The reason was that Dr. Desmond King-Hele was conducting research sponsored by the Royal Society in England to investigate the effects of the Earth’s uppermost atmospheric layers on the orbits of satellites. He had established a network of volunteers all around the world to support his work. Agust mentioned a young man, Hjalmar Sveinsson, who had worked as a summer employee for him, and who had intense interest in missiles, rockets and space research, having published several newspaper articles on these subjects. Matters started to happen quickly, and equipment, including a short-wave receiver, 7×50 binoculars (suitable for night observations), two high-quality stopwatches, Norton’s Star Atlas, and two highly accurate star atlases, Atlas Coeli and Atlas Borealis, were received at the Science Institute. Dr. Ken Fea, a colleague of Thorsteinn stopped over in Iceland on his way to the USA and instructed Hjalmar in the methodology to use. They finished the day by making an observation on one satellite after dark. On his return trip from the USA, Ken stopped by again, and assisted Hjalmar in making further observations. After that the road was clear, and Hjalmar conducted observations on many satellites that winter. In late summer 1965, when Hjalmar was scheduled to leave for England to commence studies in Electrical Engineering, he instructed Agust H. Bjarnason in the methods and use of the equipment, and he continued the observations until the fall of 1969, when he also departed to study Electrical Engineering in Sweden. After a one year’s pause, in late summer of 1970, Hjalmar trained a young man from Keflavik – whose name nobody can now recall – to resume the work. The observations were concluded in 1974 when all the equipment was returned to England. Desmond King-Hele, among other duties, was chairman of a panel for the Royal Society which sponsored these observations. He was born in 1927 and his studies included physics at the University of Cambridge. He has published a number of books on his area of expertize: A Tapestry of Orbits; Observing Earth Satellites; Satellites and Scientific Research; Theory of Satellite Orbits in an Atmosphere. He is also author of the book Shelley: His Thought and Work, Doctor of Revolution, and Erasmus Darwin: A Life of Unequalled Achievement, as well as two books of poetry. He worked for years at the Royal Aircraft Establishment at Farnborough conducting research on the Earth’s gravitational field and the uppermost layers of the Earth’s atmosphere through his research on satellite orbits. For these he was awarded the Eddington Recognition from the Royal Astronomical Society. He was appointed Fellow of the Royal Astronomical Society in 1966.

The Methodology Employed… The observations were based receiving a thick envelope monthly from the Orbits Group, Radio and Space Research Station in Slough, England. This contained a computer printout in table format with predictions of the trajectories of several satellites for the next month. On clear nights (nightfall is early in Iceland in the fall, winter and spring), and observation prospects were good, these data were pulled out, and scanned to see if any satellites were likely to be observable over Iceland that night. If a likely candidate was found, the trajectory was plotted on azimuth and elevation charts, a number of data points noted, and several computations carried out to enable the predicted trajectory to be plotted with a soft pencil in the Norton star atlas (soft so it could be erased without damaging the chart). The plot was then visually inspected to identify stars that would be close to the satellite’s trajectory. (The calculations were needed to convert azimuth and elevation data, obtained from plots of the satellite’s trajectory, into the astronomical coordinates of Rectascension and Declination used on the star maps.) Some ten minutes ahead of the predicted appearance of the satellite, the observer went outside, got comfortably situated, and used the binoculars to familiarize him/herself with the computed trajectory. When the satellite appeared, in the binoculars, it was followed until it passed between or near identifiable stars, and the stopwatch started at that moment. The observer then went back inside, and the position of the satellite when to stopwatch was started identified, usually on Atlas Borealis in Iceland. When the position was ascertained, the stopwatch was stopped on a time signal from WWV in Boulder, Colorado, which were transmitted on shortwave frequencies and therefore audible virtually world-wide. The observations were then entered into forms included in the monthly mailings from Slough, and they were mailed back to England when a reasonable number had been assembled It may be noted, that at that time the light pollution in Reykjavik was much less than nowadays. Street lighting and lighting of buildings were kept in moderation. Thus one could see twinkling stars over the city at night, and children learned to recognize the constellations. Today, things have changed, and the stars have disappeared in most cases due to the proliferation and intensity of the city lights.

Amusing Incidences… Space Research in Garðahreppur where Hjalmar lived This story originates in the basement of the old Telegraph Station, where the Science Instituted was located prior to moving to its dedicated newly built quarters. There Hjálmar, Ken Fea og Thorsteinn Saemundsson were sitting in Thorsteinn’s office. Ken was going over the observation methodology and was drawing satellite trajectories from worksheets which were used for the preparations. Around lay Star Atlases, shortwave receiver, binoculars, etc. Then a newspaper correspondent appeared to interview Thorsteinn about a Soviet satellite that was recently launched. When he saw Ken and Hjalmar along with all the equipment around them, he asked what they were doing. Ken and Thorsteinn tried to explain it for him, and mentioned as well, that Hjalmar lived in Gardahreppi, where light levels were much less that in the city, which made the observations much easier. The next day, a huge headline appeared in his newspaper, titled “The space race reaches Iceland” In the article, it is described how complex and remarkable this research was, and that the equipment required was to sensitive that even the city lights would interfere with the results. Ken, Thorsteinn and Hjalmar thought this was a most amusing story!

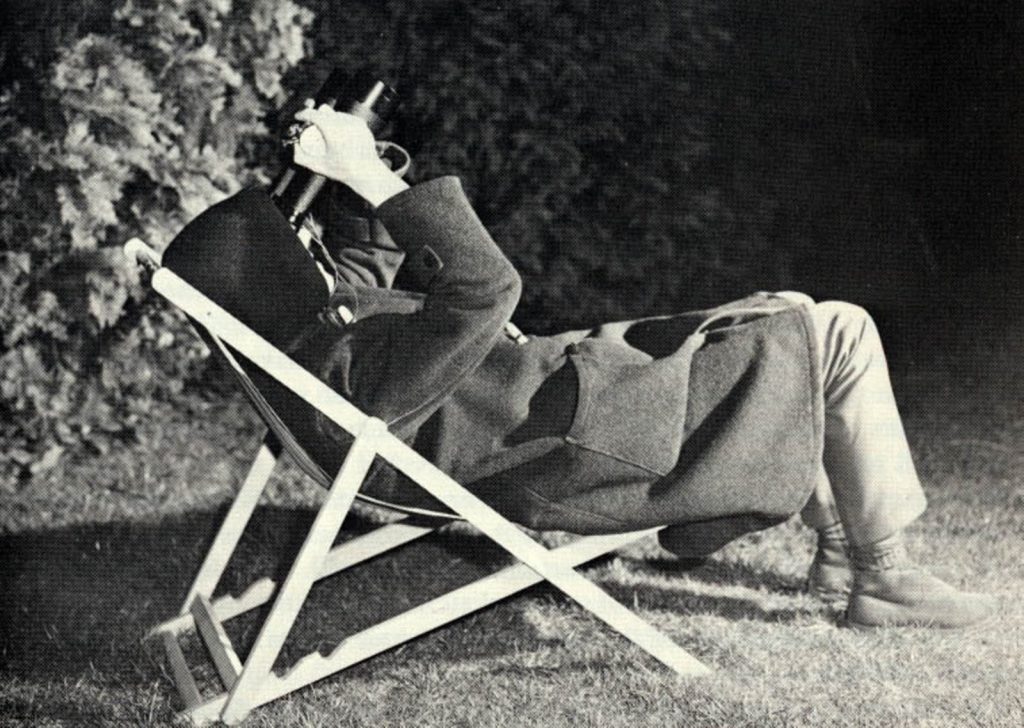

The Spy in Norðurmýri where Agust lived This story started, when Agust H Bjarnason was a teenager in Junior College. He had developed an interest in space observations from the time he observed Sputnik-1 (the very first satellite in 1957) passing overhead, when he was 12 years old. Soon thereafter, he built a simple telescope from a cardboard cylinder and, a spectacle lens and magnifying lens. With this which had a 50 fold magnification, it was possible to observe lunar craters, and Jupiter’s moons. But enough of that…. Five years later: It had drawn a lot of attention in Nordurmyrin, which about once a month the mailman brought a thick manila envelope to the house. The envelope had many foreign stamps and was marked in large black printed letters – On Her Majesty’s Service. This was considered very strange, and it didn’t detract from the suspicions, that in one of the apartments in the house lived a nationally known member of Parliament. Stories started to circulate. Somebody had spotted a suspicious man dressed in a heavy coat lying in a sun-chair in the backyard with some mysterious device which he held in one hand pointing it to the sky. In the other he held some silvery object. Sometimes he was observed furtively shining a flashlight onto a piece of paper to read some notes. Suddenly he would run inside. Someone had seen this more than once. What in the World is going on? – Mysterious mail, in the service of Her Majesty, Royal Society, and a famous left-wing politician living in the house, mysterious deeds in the back yard, strange sounds from a shortwave receiver, Morse code…This is getting very exciting… Det er gaske vist, det er en frygtelig historie! (For sure this is a scary story!) Wrote H.C. Andersen in a famous fairytale. This is not any better What it going on in this building? Later the truth became known: No big deal – This was just some dull research of the orbits of satellites. The mysterious objects the man was holding were just a pair of binoculars and a large stopwatch. He pretended to be looking at satellites. The mysterious sounds were the reception of time signals; „…”This is WWV Boulder Colorado, when the tone returns the time will be exactly”… was heard once in a while, and in between …tikk…tikk…tikk…tikk. And the young man was also a radio amateur which explained the Morse Code, which was sometimes heard late into the night, when he was “talking” to his friends around the World. This was not very exciting, but many years later, strange and terrifying events occurred in the basement of that same house, events that were filmed in the movie – “In the Myrin”!  Satellite trajectories observed in the dark of night under a twinkling starry sky. The observer is holding a powerful set of binoculars and a stopwatch for timing.

Sputnik 1 first satellite launched from Baikonur in Russia 26. October 1957.

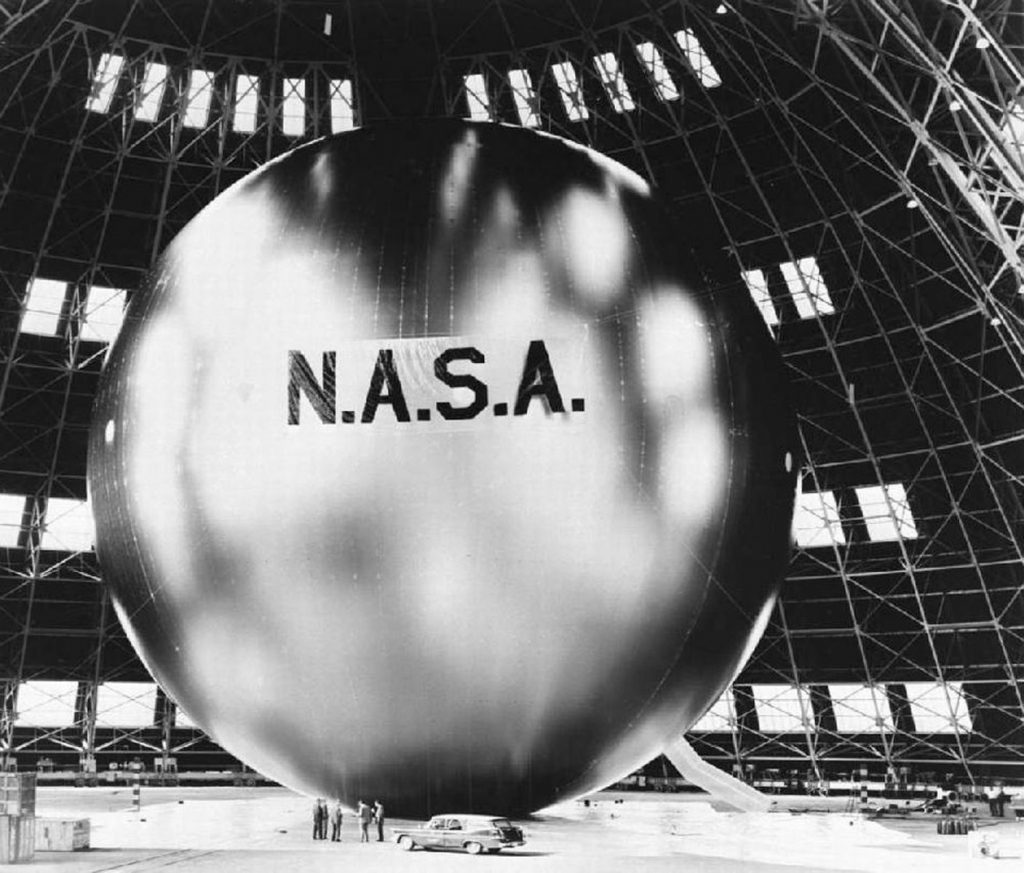

Echo 2 satellite was a metal skinned that was launched into Earth orbit and was used to reflect radio waves back to the ground.

Desmond King-Hele mathematician.

Envelopes with computer predictions on trajectories for several satellites were marked like this.

This book addresses observations on earth satellites, including with the use of binoculars.

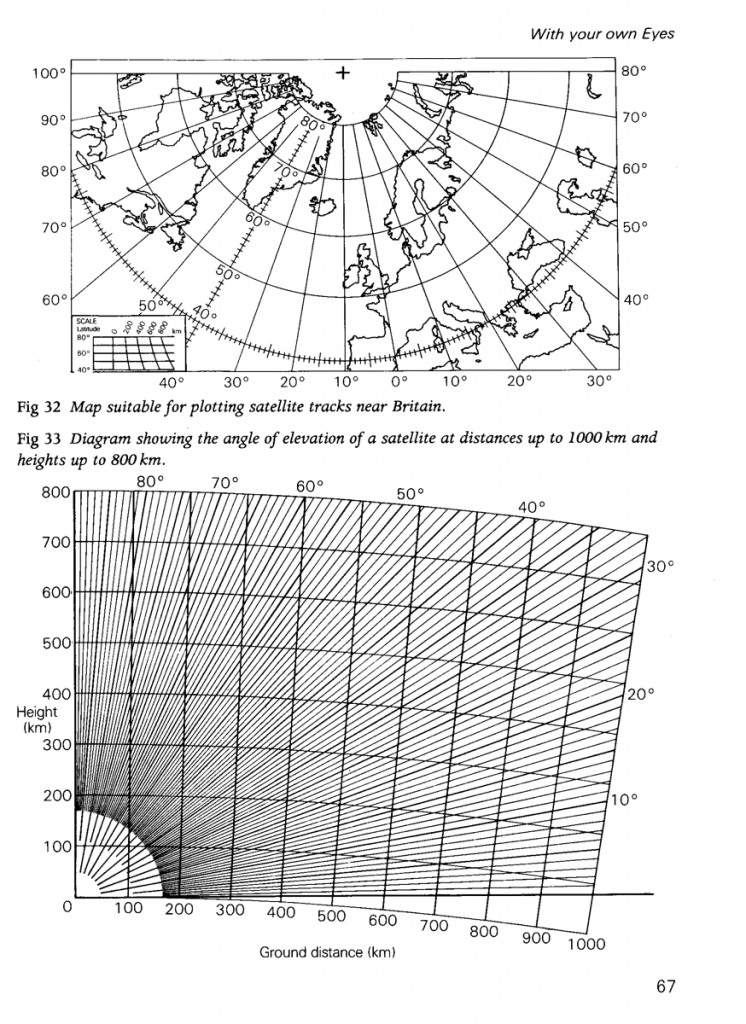

The book contains various graphs used to calculate satellite trajectories prior to observation

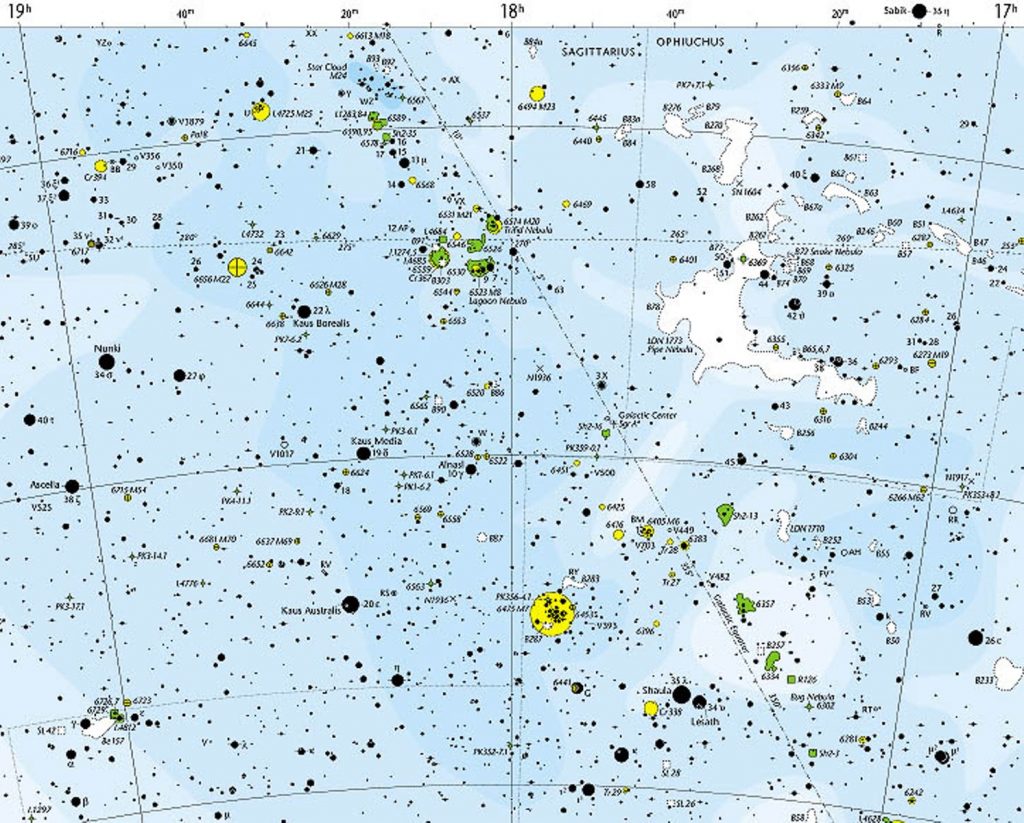

Page from Norton’s Star Atlas.

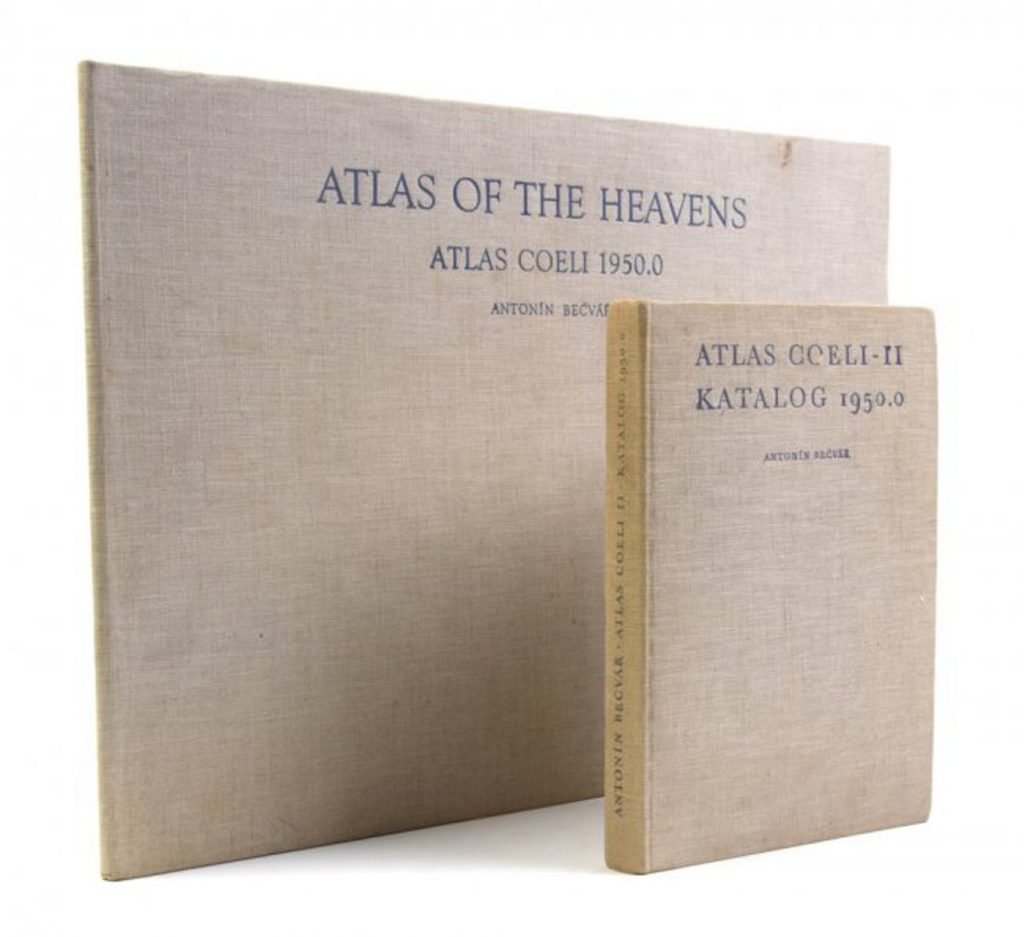

Page from Atlas Coeli Star Atlas. These were originally hand-painted by graduate students at Observatórium Skalnaté Pleso in the 1950s. They were considered to be the best available at the time of the observations in Iceland.

Atlas Coeli was in large format as seen here.

Agust is here tuning the Eddystone short-wave receiver which was provided by the Royal Society. It was used to receive time signals from the US WWV station in Boulder Colorado í the USA. It transmitted on 15 MHz which was usually the best frequency for receiving signal in Iceland. Very short pulses were sent every second, with a longer one on the minute. Precision was very important in the observations, and required a lot of practice to achieve the best results.

Different geometries for locating satellites passing near to identifiable stars.

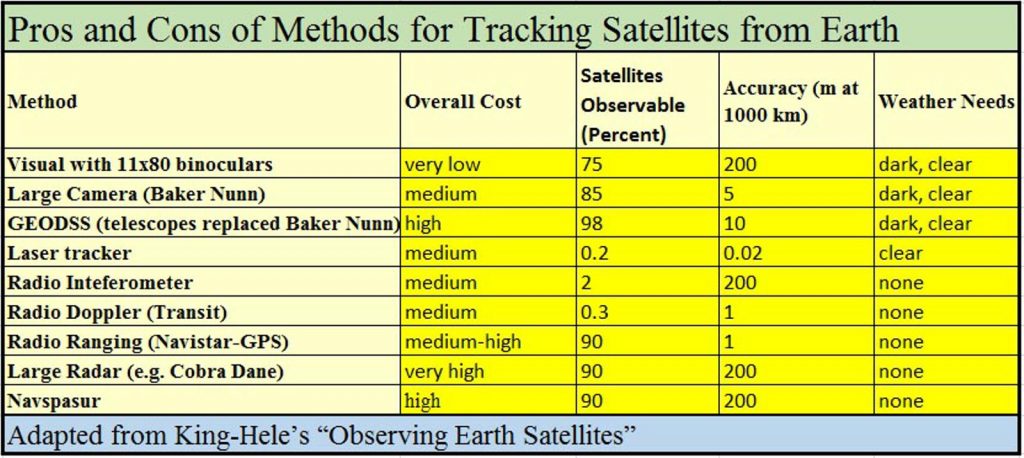

Accuracy of the observations… Accuracy of the observations is an obvious question that arises, especially in view of the simple equipment used. King-Hele said an experienced observer could achieve 1/100 of a second in timing, and about ½ degree in location We believed we achieve about 1/10 second timing accuracy, but that took some time and practice to reach. .The table below illustrates a few different methods and equipment used for satellite observations.

According to this, visual observations with good binoculars are quite accurate (200 meters at 1000 km range, i.e. 1:5000 or 0,02%), and very much more expensive and complex equipment is needed to achieve better results. In place of 11×80 binoculars we used 7×50, but then the satellites we observed were not more than 500 km away.

Finally… This report was co-operatively compiled by Hjalmar and Agust in 2015. Both are electrical engineers, Hjalmar in the US and Agust in Iceland. Reference of interest covering the space launches by the French in 1964 and 1965, which both attended can be found at: http://agbjarn.blog.is/blog/agbjarn/entry/477982/ |